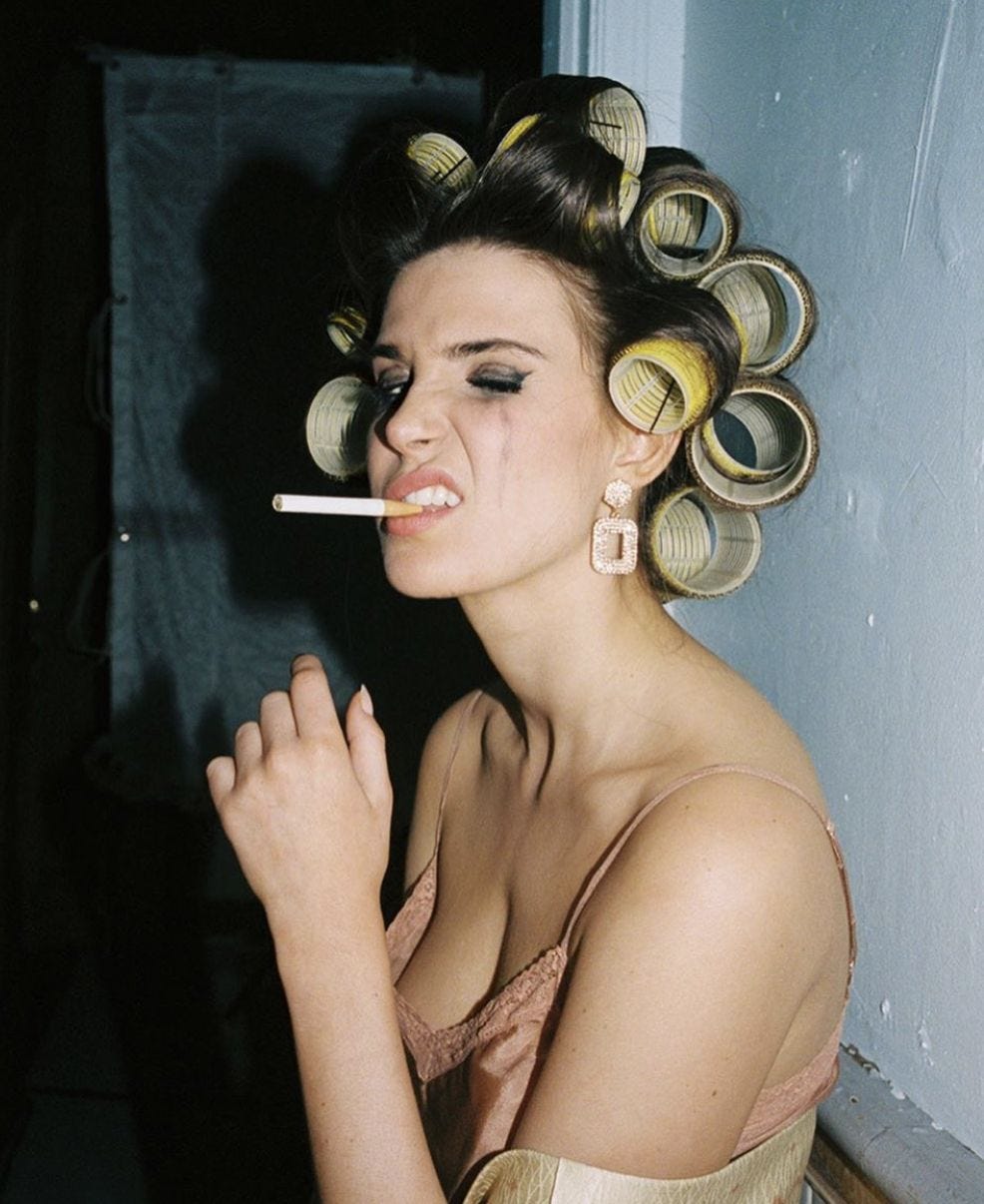

Becoming An Unlikeable Woman.

The Radical Reclamation Of Self.

“I’m becoming okay with being an unlikeable woman.”

My dear friend Sophie tells me on the phone last week. I stop in my tracks. I’m out pacing pavements, but I halt my pavement pounding and exhale audibly out of my mouth. An intergenerational sigh of resonance. Her statement hits me in my stomach, permeates my blood and lands in my bones, where it penetrates cellular memory. Good, let it live in my bones.

I realise in that moment that I am bone-tired of trying to be a “Likeable Woman”.

I realise in that moment, (I am in a season of steady epiphanies; twenty-eight is providing water-shed realisation after water-shed realisation about my own character and life, past and present) how I have spent my entire life (subconsciously of course) TRYING TO BE A LIKEABLE WOMAN. And conversely, avoiding the punishment of being perceived as an “Unlikeable Woman”, out of terror, and a bone-deep fear of rejection and abandonment.

A people-pleaser at heart (thank you, childhood wounding and my innate empathy and sensitivity), and raised in a patriarchal culture and society, which disguises itself, in many ways, as emancipated now, (at least for the white western woman) – of course I was raised to want to be a Likeable Woman! This cultural conditioning is given to us with our first dresses, and razor blades that we use to shave our legs, with our first tube of mascara, and make-up set… I could go on, and write a great critical feminist essay here.

To be honest, I will probably expand this personal essay as I read more feminist literature, and have more epiphanies about the chains around my own expression and existence. This is a lifelong conversation and process, truly. To be one’s true, mad, authentic self in our golden-chained society is already bold and reckless, but to be a fierce, loud, opinionated, fiery, take-no-bullshit WOMAN here?

That is a brave soul.

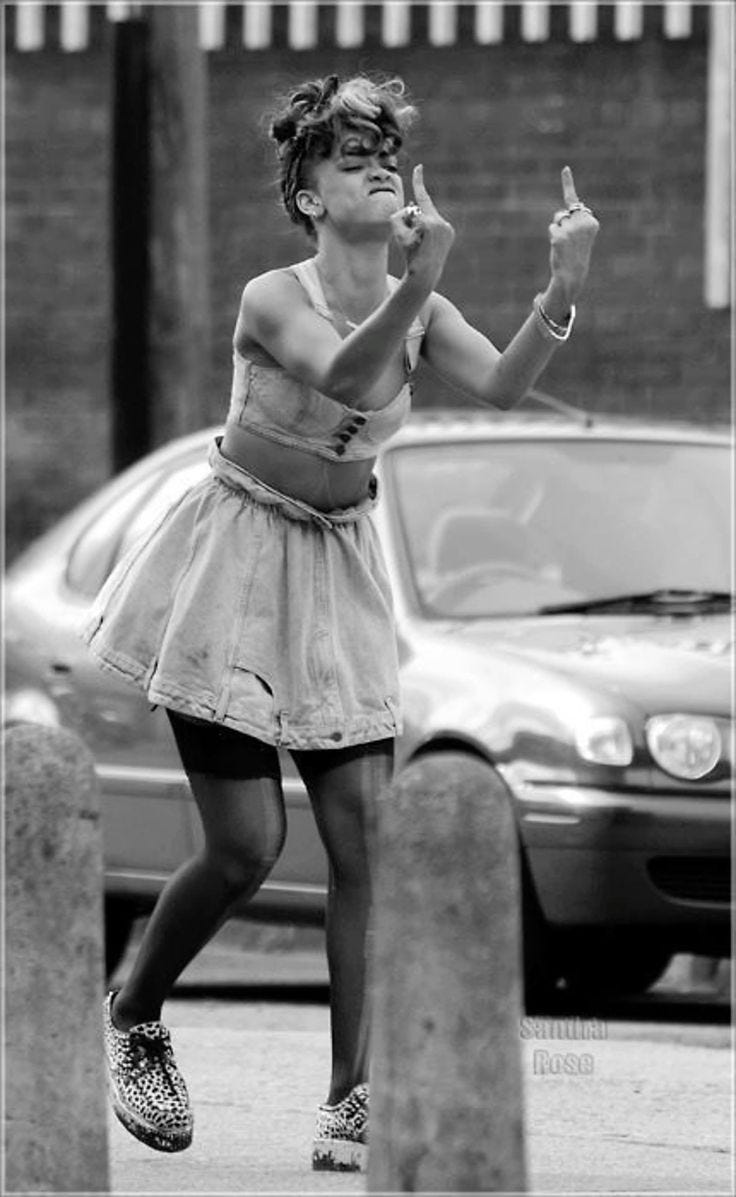

I salute every woman who dares to express herself fully.

Even in my progressive, “developed” country (I despise these western terms for the cultural arrogance they assume over what and who is “developed”, thus I should use instead the more objective term “industrialised western society”), where we have had multiple female Prime Ministers, woman in politics still receive regular death threats. Do you think Jacinda Ardern had the same job as her predecessor, John Key? Hell no.

She didn’t just have to wrangle a nation through a pandemic, and deal with the general immense responsibility of being the puppet of a country’s governance (there are obviously many silent powers pulling the strings behind any nation’s leader). She also didn’t just have to raise a child simultaneously. She was scrutinised and criticised in her every move in a way that men in power here are just not, by the media, and the people alike. She was sent active death threats throughout her prime ministership.

Just like Golriz Ghahraman, a former Member of Parliament here in New Zealand for the Green Party. Ghahraman was also our very first MP elected from a refugee background. Formerly a lawyer for the United Nations, Ghahraman was also an outspoken, left, brown woman, who was a loud advocate for human rights in our country. The woman received steady death threats throughout her career. Can you imagine? Her very existence and voice clearly angered a small group of very insecure and very angry people. Ghahraman lies at the intersect of sexism and racism – she is both woman, and a person of colour, and thus bore the ugly consequences of being both, within the structure of colonial white patriarchy.

I have never heard of male politicians in this country receiving so many death threats as our outspoken women. Patriarchy and misogyny are invisible beasts at work – we cannot point our finger to any obvious angry demon who lives at the top of a dark castle and eats women for breakfast; it is an invisible system of oppression, much like racism and white supremacy. (I would like to point out however that many of the most powerful and rich, billionaire class of people in this world are both male and white). Most men wouldn’t think that they are misogynistic, or have traces of misogyny in their blood, but it’s a beast that will influence their behaviour in all sorts of unconscious ways, if unchecked.

The liberation from oppressive systems requires much individual and collective work.

Meanwhile, gender pay gaps still exist globally, much of woman’s labour is still unpaid (care work), and most disturbingly obvious, (to any female or identifying-female reading this), women still walk around at night with our car keys between our fingers. Women still live in terror that we will be assaulted for exercising our basic human right – to exist. Yes, even in modern, progressive Aotearoa, New Zealand, the first nation to give women the right to vote! And yes, I am aware that things are much, much worse for many women in many other countries, but that debate is a futile one – like comparing trauma, trying to determine which is of the lesser-evil, or which genocide is less awful than another, for example.

All genocide is evil. The ceaseless abuse and murder of women, and any innocent, anywhere, is evil. Let us just agree that debating which suffering is worse on the planet is a waste of energy. Let us use our energy and imaginations instead for conversations around liberation.

I have begun my essay with political evidence, and to make the darkest point of all – of course we women fear our fullest expression, and being disliked, or even hated – because it may cost us our very life.

It wasn’t so many generations ago that my own ancestors were burned at the stake by a group of angry, fearful men in the witch trials that occurred in England between the 15th and 18th centuries. Still today, women are raped and murdered at alarmingly higher rates than men, with the WHO estimating that 1 in 3 women have been, or will be, subjected or subject to either physical or sexual abuse by an intimate partner or non-partner in their lifetime.

Harriet Sherwood wrote in a Guardian article from 2022 titled “Early modern witch hunts left Britain with collective wound” - “thousands of women were accused of witchcraft in the UK and Ireland between 1450 and 1750. Many were tortured until they identified relatives and neighbours as witches; those deemed guilty were hanged and, in the case of Scotland, their bodies then burned” (2022).

This period was known as “the burning times”. I imagine that this trauma is only truly being reconciled now, in the rage of the modern woman. We may look far more emancipated than our predecessors, but we are still terrorised into some form of patriarchal submission or another. As museum exhibitor curator Cali White states in the article, “Our whole nation was traumatised and divided by what became a mass hysteria, passed down over generations. The legacy of this has left a collective wound which affects us all in some way, and which we are now being called to understand and heal” (2022).

I recall studying this time period in History, in my final year of High School. I only studied this subject at all because I had chosen History and to specialise in humanities subjects, and my own teacher had selected the topic out of many that he could have taught us. The same goes for the colonial history of my own country – I only ever learnt anything about it because of my scholarly ambitions and interest in history, English and culture. Most of us are not taught our own history, and its tales of trauma. Without teaching and acknowledging history, we can never truly understand the complexities and the suffering of the present moment.

The same goes for understanding the way capitalism and colonialism are inextricably intertwined, as two sides of the very same coin – you had to seize the commons, or communal land, first in order to “own” it, (capitalism), and then you could go steal everybody else’s around the world, (colonialism), under the guise of “progress” and “civilisation” and “taming the savages”, and all that evangelical jazz.

The untold history lesson of the time period of burning “witches” was this: any woman who challenged the authority or power or corruption of the church or state was eradicated.

Murdered.

Women learned that they must zip their lips, if they wanted to live, and the unruly, outspoken, vocal and rebellious women were actively tortured and murdered. Entire towns were encouraged to watch as innocent women were burned and hung, during a plague of mass hysteria, and essentially, patriarchy’s fear of these satanic “witches”.

Let us now discuss the etymology of the word “witch”. The word “witch” was clearly weaponised by patriarchy from the 15th century onward – we can all easily conjure a comical, cartoonish image of a woman with a black pointed hat, warts on her large nose, a wicked smile, grey hair, with a cauldron, perhaps about to boil some child for her dinner. This image was one of propaganda, sold to us by the church and state from the 15th century onwards in Britain. It has permeated our fairy tales rather well, and is still a strong symbol in modern society, of an unruly, unkept, mean old hag, who probably lives in nature, alone.

In reality, this woman is, and always was, any female healer, or rebellious woman who chooses not to marry and reproduce. Perhaps she is a scholar, or an artist too, and a general recluse. Perhaps she just enjoys her solitude.

Clarissa Pinkola Estes writes in her classic Woman Who Run With The Wolves that the word witch is derived from the word wit, meaning wise. “Like the word wild, the word witch has come to be understood as a pejorative, but long ago it was an appellation given to both old and young women healers, the word witch deriving from the word wit, meaning wise. This was before cultures carrying the one-God-only religious image began to overwhelm the older pantheistic cultures which understood the Deity through multiple religious images of the universe and all its phenomena” (1992).

I have never forgotten this reclamation of a definition, since I first read Este’s iconic book, several years ago. Nowadays, we live in the modern reclamation of the word “witch”, at least for the young and progressive. As I write this, I hear Alice Phoebe Lou’s “Witches” song play in my head, “I’m one of those witches, babe! I’m one of those witches, babe! Just don’t try to save me; I don’t wanna be saved!”.

Back to the topic at hand. There is a reclamation at work of the word witch. And women, everywhere, around the world, are rising. One could say: the feminine (energy) is rising.

Now that we have briefly covered some political stuff, and briefly glided over a long and complicated history of women’s murder and oppression in just one cultural lineage (we haven’t even acknowledged how recently in history women were given the right to vote around the world either), it is easy to see why women do not fully express ourselves. We carry an ancestral, and still current, fear of being killed for our very self-expression. I’d like to now discuss the implications of not expressing oneself fully and the impact that self-censoring has on a woman’s health.

As aforementioned, we women are conditioned into being people-pleasers and emotional regulators since before we can talk. Girls who are loud and gregarious and vivacious are called things like “precocious”, in a negative sense, or “bossy”, or “loud”.

We are enculturated, from a very young age, to be “good girls” – to put others first, to be selfless, to be kind, to be forgiving, to be mild and meek. To be good little housewives. No, this is not the 1950s, and it is true that nowadays we can be as educated as men, we can be CEOs, home owners, and we can wear pants too. But still, according to the physician, Gabor Mate, women have 80% of all autoimmune diseases in our society.

“Why?” Mate goes on to answer his own question:

“Compulsively concerned with the emotional needs of others, rather than their own, identified with duty role and responsibilities, their work in the world rather than their own true selves, they tend to suppress healthy anger, so they tend to be very, very nice, and peacemakers, and they tend to believe that they are responsible for how other people feel, and that they must never disappoint anybody – two fatal beliefs.

So these are the people… that according to my observation, and according to a lot of research as well… these are the people that tend to develop autoimmune diseases. Now in this society which gender is more acculturated, programmed to suppress their healthy anger, to be the peacemakers, to be the caregivers? Women. This is the function of a reality that a lot of people deny, but it’s a patriarchal society.”

The psychologist Maytal Eyal summarises Mate’s point succinctly in her essay in Time, aptly titled: “Self-Silencing Is Making Women Sick”.

““Be more disappointing” is not a piece of advice most people would pay money to hear, but in my therapy office, it’s often the most valuable guidance I can give. My clients are mostly women, and nearly all of them struggle with a fear of disappointing others” writes Eyal. “Our culture rewards women for being perpetually pleasant, self-sacrificing, and emotionally in control, and it can feel counterintuitive for my clients to say “no”—or firmly assert their wants and needs. But my work is about helping them realise that their health might literally depend on it.”

She goes on to further emphasise Gabor Mate’s point – that modern women are suffering the lion’s share of autoimmune diseases – from chronic pain, insomnia, fibromyalgia, long COVID, irritable bowel syndrome, migraines, and are even apparently twice as likely to die from a heart attack. Women also suffer depression, anxiety and PTSD at “twice the rate of men, and face a ninefold higher prevalence of anorexia, the deadliest mental health disorder.”

She argues that these disparities cannot be explained by biological factors alone (genetics and hormones), but must be examined from a psychological perspective, citing studies beginning in the 1980s to the modern day that point to this thesis: the suppression of a woman’s voice, and her needs, is making women sick.

“Specifically, it seems that the very virtues our culture rewards in women—agreeability, extreme selflessness, and suppression of anger—may predispose us to chronic illness and disease.” These enculturated, deeply engendered traits can even lead women to premature death. A study following 4000 people over ten years in the USA found that women who didn’t express themselves when they had fights with their spouses were four times more likely to die prematurely than those who did, even after other factors like age, blood pressure, cholesterol and smoking were taken into account!

Eyal argues that it can be difficult for women to break out of this paradigm – to become Unlikeable Women – as I am proposing, because it is swimming against the cultural current of the mainstream. It is doing the opposite of our conditioning. She writes about the fear of women in her clinic even admitting their right to their own feelings and needs, because of the strength of the cultural forces that reinforce their martyrdom. Every young woman I know doing the work of decolonising themselves, or of liberating themselves from these deeply engrained belief systems will attest to how difficult this work is.

But the price is our health, it seems.

As a young woman of her late twenties, who has just been hospitalised for medically unexplainable stomach pains last Spring, and with a family history rife with women (in particular) with autoimmune diseases, I for one am no longer taking this work lightly. For me, being a “good girl” is all I have ever known. Although stubborn, determined, and brazen by nature, (in that I was never a demure, quiet, wallflower type of girl, and I have always been one to challenge belief systems and injustices I find problematic), I have still found myself a people-pleaser for most of my life, with poor boundaries.

I grew up conflict-averse outside of my family, always the mediator, physically upset to my stomach by other people’s discomfort, conflict or upset. Being innately sensitive and empathetic, like many of my dear female friends (birds of a feather flock together, as they say), I tend to internalise, digest and metabolise not only my own emotions, but the emotions of others around me too.

I was also an overachiever all throughout my formal education, always doing excellently in school and my extra-curricular activities, never rebelling against authority, always desperate for approval and validation. I think the most rebellious thing I did to my parents, (by societal standards) was take a gap year to travel instead of commencing university straight away. Or at twenty-five, turning down a good government job to pursue a yoga teacher training and have an exhibition of my film photography from Mexico, taking other, less professional jobs in order to do so, was rebellious for me.

Don’t get me wrong, in many ways I am a bold, adventurous, modern feminist woman; I have travelled the world alone, I have moved countries alone to both study and work, and I have vocally attested to misogyny, racism, and various other socio-political issues this decade, and the last, in all sorts of places. I have a loud voice, I am a chatterbox, and I am not considered shy, or timid. I enjoy debating self-righteous men, or any human who is too sure of the correctness of their belief system. (I am aware that I am also an opinionated human with strong belief systems, but I love scrutinising them constantly myself, and questioning my own assumptions often).

Despite these personality traits, I am still, in many ways, self-conscious, insecure, and a recovering people-pleaser. This year one of my few intentions is to learn proper, healthy boundaries. If my dating life of this decade has taught me anything, it’s that I over-give energy and love without proper discernment, and assume the role of “healer” and “therapist” of the men I am so often drawn to. I see their potential, wounds and all, and I try to fix them – an archetype that many of my female friends also identify with. I give and give and give until I am depleted and exhausted. A boy I once dated several years ago, who was brilliant, but deeply troubled, even had the audacity to point this pattern out to me (he later told me that I had helped him love himself, and after we dated finally went to therapy).

As my friend Sophie so eloquently put it – “You and I are so used to helicoptering people’s feelings and emotions and catering to how they feel about us, as people-pleasers, desperately seeking others approval, that we bury who we are in fear of being rejected, of not being accepted and loved”. This pattern, though particularly evident in our romantic lives, was largely unconscious to Sophie and I, and to so many of my female friends, until the last few years, or until a phenomenon known as “The Saturn Return” – or the hitting one’s late twenties.

Suddenly, it has all become abundantly clear to many of us, after health breakdowns, or mental breakdowns, or particularly nasty break ups. Or all of the above.

My realisation, of my own deep fear of being and becoming An Unlikeable Woman has only fully dawned on me recently, post break up, and breakdown. (The physical kind, where I am seeing gastroenterologists and gynaecologists, the psychological kind, where I am seeing a psychiatrist, and the heart-breaking emotional kind, where one really sits with the root of one’s pain). I realised upon being hospitalised last September that I did not want to develop an autoimmune disease or cancer, which as aforementioned, plague both sides of my family, as a cost of the way I was operating.

I am physically still checking my body for root causes. But should nothing arise, or no clear-cut diagnosis like “Oh she is just a celiac, that is what it was!”, then I have to consider the whole story – including the narratives of my conscious and unconscious psyche, or my base belief system. I think we often have to be completely broken down, egoically speaking, to truly change. I am not saying that my people-pleasing tendencies or personal trauma hospitalised me last Spring. But I am also not, not saying this.

For me, a large part of challenging my own fears around being perceived negatively, or judged, or misjudged, or being even, god forbid, being an Unlikeable Woman, is sharing my writing publicly. Finally, after all these years. Airing my opinions, like the many shared in this essay, opens me up for judgement, for your judgement, dear reader.

I have always held many opinions that challenge or counter mainstream thinking, across many fields. I have always been a cultural critic, to some degree, and my studies in critical theory, political science and philosophy broadened my ability to think critically, and to question societal narratives disguising themselves as universal truths. I try to think like an anthropologist.

My beliefs range from radical to more mainstream, and though I always try to hold nuance, and multiplicity, (in that various opposing truths may coexist) parts of me still fear the ostracisation of being labelled a mad, crazy woman. Or another angry feminist. You are familiar with these labels, I’m sure, and these archetypes. But do we ever stop to consider why some women are so damn angry? That our anger could be justified?

To be fair, most of my heroines were indeed labelled just this – fierce, crazy feminists. They were brazened, intelligent women who challenged power and society and who spoke truth and sanity to lies and insanity, in my opinion. These figures in history have always been ostracised and criticised and misunderstood by the masses, and suffered consequently. Think of all of the poets and saints and sages across history, of all of the mad artists, the ones we now remember fondly, the ones we still read, looking for wisdom and truth. Most were misunderstood in their time, and often not very popular.

Most parts of me acknowledge now, with compelling evidence, that I have a duty to speak my truth, my needs and to honour my feelings, knowing that self-censoring only damages my health. Yet I will admit, a part of me still fears that I will be rejected and expelled from society if I do – a hangover from history. Every essay I publish I exercise my own voice, and I honour my own self-expression. Yet every essay and opinion I air on the internet also offers more and more material of myself to be judged and misunderstood and rejected from the collective. It is a double-edged sword.

But I must learn to become okay with being Unlikeable!

For most of us, the work of healing the people-pleaser within, and of healing our minds, hearts and bodies, and becoming okay with being Unlikeable to some, comes simply by learning boundaries. As my friend Sophie summarises, it entails “…saying no more. Having boundaries. Triggering people”. The notion that we can trigger, even offend people, in the honouring of our truth is RADICAL for most women I know. Paradigm shifting, even. The balance here of course is respect, and not being, frankly, a self-entitled asshole.

The paradigm shift, of course, is the process of individuation, of genuine self-esteem building, which leads to healthy self-respect. The term “self-love” has been a little hijacked by modern commercialisation, eliciting fluffy images of bubble baths, eye masks, chocolate bars and nail polish. And whilst these practices of self-care can indeed be acts of self-love and kindness, such as the carving out of time and space to run oneself a bath and rest, I would argue that the true work of self-love, or self-respect is much simpler.

My therapist, yoga teachers, and most wise mentors I have ever had or known all echo the same truth: the work starts with being kinder to ourselves. The work begins with noticing our incessant inner critic and judge and militant drill sergeant, and offering ourselves instead gentleness, grace, and empathy, as we would a dear upset friend. The work is mothering ourselves better, of re-parenting ourselves, of giving ourselves the validation and affirmation that we all deserve, the dignity that we all deserve – to be seen, heard, accepted and loved, unconditionally.

We are still worthy human beings even if we failed, or fell short of our goals, or did not accomplish everything on our to-do list for today. Learning to self-soothe, and self-regulate, when we are dysregulated or taken over by currents of strong emotion, and negative, self-critical thinking patterns is a vital skill for the health and wellbeing of every human being.

As Eyal writes, “it can be paradigm shifting to understand that behind every emotion exists a need. Anger, for example, can signify the desire to change our current circumstances. Rather than women treating our emotions as inconvenient, bodily malfunctions best to be muted and ignored, we can ourselves to view them as windows of insight.” Instead of “casting away our anger”, she writes, (or sadness, grief, overwhelm, depression, etc) “a valuable question we can ask ourselves in moments of frustration is: what am I needing right now?”

What am I needing right now?

What a question for self-reflection, inquiry and understanding.

What a kind question, a question that emerges out of self-respect.

As aforementioned, another vital practice for a woman’s health and wellbeing (and any human’s health and wellbeing for that matter) is boundary setting. Whilst this topic is large enough for an entirely separate essay, it is an essential practice for becoming An Unlikeable Woman, and a healthier, happier woman in general!

“For women, who have been unconsciously taught to view our likability as our greatest asset, boundary setting can often feel counterintuitive”, Eyal writes. “Many of us fear that if we honestly communicate our needs and limitations, this will threaten our relationships. But it’s the contrary that’s true: when we set heathy boundaries… our relationships actually become stronger and healthier.”

Creating and maintaining healthy relationships is essential for not only our social, but physical health and well-being. One meta-analysis depicted that those with strong, supportive social relationships live longer, or have a 50% lower risk of a premature death. Healthy community is essential to our health, as are healthy boundaries around our time and energy.

So, in conclusion, let us acknowledge the bravery it necessitates to be oneself, and to be okay with not being liked, or for that matter, understood, or accepted. Let us acknowledge the healing work it takes to get there, and the pain one must traverse through, the wounds one must face. Let us acknowledge our personal and collective ancestry, or the many, many lives that came before us, and the intergenerational gifts and wounds we inherit. Let us acknowledge ourselves, and our own growth, our own patterning and conditioning, and our own becoming.

Let us see that not being ourselves could cost us our own health and vitality. This brave process is one of peeling back, layer after layer, to return to the truth, or the core of who we are – which I believe, is one of goodness. My chosen title for this essay was a rebellious one – because who tells us ever in our lives to strive to be more Unlikeable?

And of course, I am not implying that you should seek to irritate or upset others for the sake of it. But I am advocating that we become okay with upsetting others if it is a consequence of being fully ourselves, of speaking our own truth. I am also advocating that we become a better friend to ourselves, that we seek to truly know ourselves, and that we learn to love ourselves, warts and all.

Learning compassion for all of the parts within, the parts we like, and the parts we do not, can only ever benefit the world – as we can then begin to expand our tolerance and capacity for compassion for all the humans we encounter – the ones we inherently like and understand, and the ones we do not.

Becoming okay with being Unlikeable is essentially a radical reclamation of Self.

And this work is a gift to the collective, as our authenticity inspires other’s authenticity, and healing - and the world is better for it.

We don’t need more martyrdom and suffering for collective liberation, perhaps we need to begin by liberating ourselves through compassion, and permitting ourselves the full expression of our own magic and madness (without causing others harm in doing so, I should caveat).

Becoming Unlikeable is liberating the Self.

References:

Blaut, J. M. (1989). Colonialism and the rise of capitalism. Science & Society, 53(3). https://philpapers.org/rec/BLACAT-4

Estés, C. P. (1992). Women Who Run with the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA26882678

Eyal, M. (2023, October 3). Self-Silencing is making women sick. TIME. https://time.com/6319549/silencing-women-sick-essay/

Harvey, M. (2020, September 22). Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern has received death threats on social media. NZ Herald. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/prime-minister-jacinda-ardern-has-received-death-threats-on-social-media/7ML4OZDID6YKZHQ3Q3YZS33KGU/

Holt‐Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social Relationships and Mortality Risk: A Meta-analytic review. PLOS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

Mate, G. (2024). Sarah Wilson on Instagram: ‘For the Women out There with #autoimmune Disease. Take from This @gabormatemd Interview with @thediaryofaceopodcast What Helps You Make Sense of Things and Brings You Soothing Relief from Your Pain ❤️ #hashimotosdisease.’” www.instagram.com/p/Cz4Y4GKsCRS/

McClure, T. (2023, January 20). Jacinda Ardern: political figures believe abuse and threats contributed to PM’s resignation. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jan/20/jacinda-ardern-speculation-that-abuse-and-threats-contributed-to-resignation

Pay reporting for gender equality. (2023). In OECD eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1787/98f730ec-en

Rawhiti-Connell, A. (2024, January 16). Golriz Ghahraman’s resignation raises questions about life in political spotlight. The Spinoff. https://thespinoff.co.nz/the-bulletin/17-01-2024/golriz-ghahramans-resignation-raises-questions-about-life-in-political-spotlight

Reporting Gender Pay Gaps in OECD Countries: Guidance for Pay Transparency Implementation, Monitoring and Reform. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/ea13aa68-en/1/3/1/index.html?itemId=/content/publication/ea13aa68-en&_csp_=cb036b49c30b2b5e419ca33b85864294&itemIGO=oecd&itemContentType=book#section-d1e291-a098711249

RNZ News. (2024b, January 16). Former Green MP Golriz Ghahraman subject to “continuous” threats whilst in Parliament - Shaw. RNZ. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/political/506852/former-green-mp-golriz-ghahraman-subject-to-continuous-threats-whilst-in-parliament-shaw

Seedat, S., & Rondón, M. B. (2021). Women’s wellbeing and the burden of unpaid work. The BMJ, n1972. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n1972

Sherwood, H. (2022, January 3). Early modern witch-hunts ‘left Britain with collective wound.’ The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2022/jan/02/early-modern-witch-hunts-left-britain-with-collective-wound

Silencing the self across cultures. (n.d.). Google Books. https://books.google.co.nz/books?hl=en&lr=&id=Y39MCAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA399&ots=I5TNawDl1c&sig=PeEfN939i55wkneI_J6YSTb6KbI&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

World Health Organization: WHO. (2021, March 9). Violence against women. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

Yep yep yep. It took me until my mid-30s to realize that it was a good sign if some folks didn’t like me. Still learning this lesson in more nuanced form. Where do we want to put our limited energy? Into trying to perform for others or for doing what is right and good for our body?

And it’s quite the process of becoming aware of the emotional hooks via the un- or semi-conscious manipulation of others who are projecting their own pains onto us.

Beautifully written, as always, Laura. Really blown away by your skill.

All completely spot on, Laura, and very well said!! (Great pic at the end too 😁)